Breathe or Do Not Breathe, There Is No Try

In this post, BSP Coach Alex Williams, discusses the importance of proper breathing and the effect it has on performance, recovery and daily activity. He also goes into detail on strategies to control breathing patterns.

I’m pretty sure that’s a direct quote from a jedi master in Star Wars… No? Well, close enough. Fortunately for us breathing is an involuntary process that occurs in the body. We don’t try to beathe, it just happens. We don’t have to actively think about contacting and relaxing the diaphragm in order to expand our lungs or exhale, and we don’t have to actively think about how we are exchanging oxygen for waste within the lungs (although that would be pretty wild to be actively in tune with something so microscopic). Breathing is a survival mechanism, but due to the lack of attention paid to it many of us have become really bad at it.

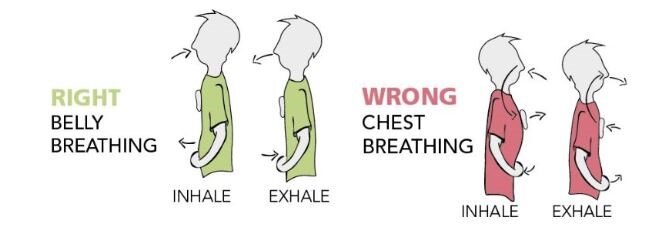

Humans are built to be “belly breathers”, yet many of us now are subconsciously “chest breathers”. Watch an infant breathe, it’s like clockwork how far their stomach expands as they inhale and then contracts as they exhale. How do you compare? Why is meditation so calming? Listen to how often breathing is cued. By relying on chest breathing we decrease the efficiency of our respiratory system. When we breathe with our chest we essentially ask the lungs to do the same work with half the capacity. Not entirely what we’d categorize as efficient. Luckily our body is phenomenal at making order out of chaos, however, this is not a new norm that we want as it can have adverse affects that will be explained in this blog.

Although our lungs function in a largely unconscious fashion, there are things we can do consciously to restore some our our lung’s capability to perform.

Let’s first talk about what is happening in the body when we are a chest dominant breather versus a belly dominant breather. A belly breather is primarily using the diaphragm and abdominal muscles to expand and contract the lungs. This allows the lungs to inhale and exhale to their maximum capacity. In turn, the body is able to take in the greatest amount of oxygen and rid the greatest amount of carbon dioxide it is capable of in one breath. Sounds awesome, right! So why would we settle with compromising that process? When someone is a chest dominant breather they instead rely on the muscles surrounding the ribcage. This restricts the ability of the lungs to expand which then restricts the gas exchange that can take place.

When the lungs are restricted and unable to do their job it creates stress within the body. This turns on the sympathetic nervous system, the engine of stress. A viscous cycle of stress and short, inefficient breathing is then the new norm. Short breaths create stress, stress creates more short breathing. On the other lung (bad pun), when we are able to use the lung’s full capacity our body relies more heavily on the parasympathetic nervous system which induces a more relaxed state. In short, chest breathing can have adverse affects on many body functions due to the stress it causes inside the body.

Some of you may be wondering how this pertains to sport or training. In all of sport or training, there is likely going to be some element of chaos or excitement. This can be good or bad. Depending on the situation the athlete may need to get amped up with the situation or to calm themselves down in order to be sharper mentally. Being aware of your breath can help you in these instances. It can also be important to know when to breathe during training. Think of a goblet squat, for example. For someone inexperienced this can be a new and unfamiliar position. Due to the front-loaded nature of the exercise your abdominals are contracting in order to keep your spine upright. When the abdominals are contracted the diaphragm also is contracted, which decreases lung capacity. If the athlete is unaware of how or when to take a breath in there can be some confusion and struggle and maybe some rosy cheeks that show up. As a general rule of thumb, inhale on the relaxation and exhale on the contraction. So for the athlete going through a goblet squat they would want to inhale as they lower (eccentric) and exhale as they forcefully contract (concentric).

So how can we help reverse this internal trend? By thinking more about our breathing. We don’t need to take time out of our day to set aside breathing practice, however, being more conscious about how you’re breathing perodically can help return the body to a more natural and calmed state.

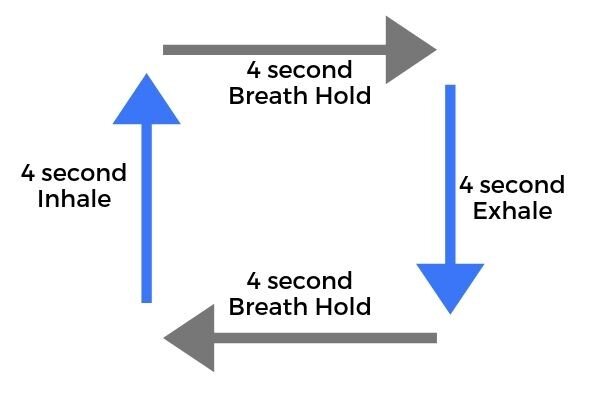

There are a few strategies that you can start with. The first one is called Box Breathing. Box breathing is a strategy used by Navy SEALS to help train them to control their breathing during high-stress situations. In this article Mark Divine, a former SEAL commander, demonstrates the technique further. The premise of Box Breathing is that you slow the process of the breath down by adding time to each portion of the breath. An example of this would be a 4 second inhale followed by a 4 second hold, then a 4 second exhale with another 4 second hold. The inhale, hold, exhale, hold create the box. During the inhale the focus is on gradually filling the stomach with air first before expanding through the chest as well as using the entire time to inhale. During the exhale the focus is on trying to empty the lungs completely by contracting, or squeezing the abdominals in order to push air out. Think about pushing your stomach to your spine. For added difficulty, try this laying down on your back. The second strategy is the tactical breath. It is similar to Box Breating in that it focuses on a controlled inhale and exhale with a pause in between, but the timing on this one is usually a 1:2 ratio of inhale to exhale. So if you inhale for 2 seconds, you’d exhale for 4 seconds.

As I stated earlier, these are not drills you have to take a lot of time to do. You can do these sitting at your desk or walking to your car. A great time for them is right before bed, or even laying down in bed. Start simple, get used to inhaling and holding an expanded stomach for a few seconds before going on to three, four, or even five seconds – it’s harder than you think. Get used to this timed system of breathing then gradually increase the time you spend on the inhale or exhale.

As you get more and more proficient in this you may even start to notice your natural breathing pattern becomes longer or more diaphragm focused.